Intructions

- Don't even bother washing your fibers unless they are really dirty, and in that case, I don't know how to help you without creating tangles. Yes, the fibers are coated in a natural waxy cuticle, but it just doesn't seem to matter whether you wash that off or not.

- Carelessly comb your fibers into loose logs or card into loose rolags. Loosely, so that you have an easier time getting the fibers saturated in dye. The rest of these instructions assume you have one ounce of fiber prepared in this way.

- Put your safety gear on, including but not limited to goggles, gloves, and face mask.

- In a container that is easy to pour from, dissolve 1 1/2 teaspoons of urea in a 1/2 cup of water.

- Measure 1/2 teaspoon of dye into a small dish. (With the exception of dyes marked * or ** Scroll to the results section for an explanation.)

- Add a little bit of the urea-water to the dye and use a palette knife to paste up.

- Add the paste-up to the urea water and stir until complete dissolved.

- Dissolve 1/2 teaspoon of soda ash to the dye mixture.

- Pour the mixture into a quart-sized resealable bag.

- Stuff some of that cotton in there.

- Overcome your emotions, such as doubt, regret, and fear. You will make it all fit. Try prodding it and squishing it with your gloved hands as you go.

- Seal the bag while carefully squeezing out the air.

- Massage the bag gently without ripping the bags. Make sure you penetrate all fibers. You can check by opening the bags, but be prepared for a mess.

- If your dye has turquoise in it, put the bag in a pot of warm-hot water to bring out the greener hues.

- Let those bags sit overnight.

- Rinse fibers until water runs clear. Please consider methods to save water. I actually took a shower with my fibers in a wash basin. After the first rinse to get the bulk of the excess dye out, I let the fibers soak with some professional textile detergent for about a day before doing a final rinse.

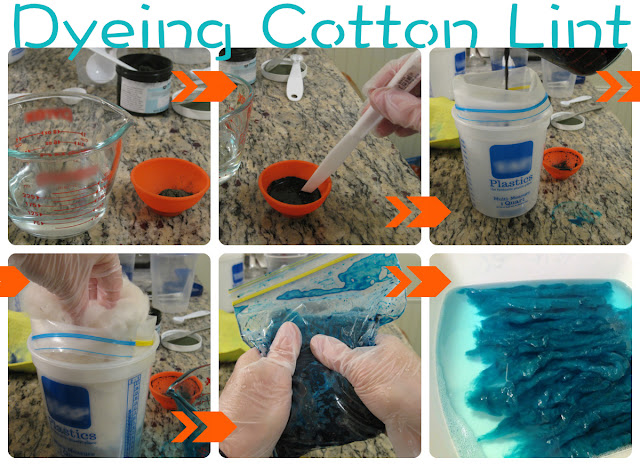

The above graphic might give you a little insight into my process and what sort of supplies you will need to gather. Speaking of which:

Supplies

Consumables:- Cotton lint, either still in the boll, on the seed, or ginned. No sense in buying it already combed since you are going to make a mess of it.

- Fiber reactive dye

- Soda ash

- Urea

- Professional textile detergent (optional)

You'll notice that the minimum amounts offered are not only cheap, but more than enough to complete this project, so I don't know why people even bother with the sub-par dyes available at craft and grocery stores for what is going to end up being a pretty labor intensive endeavor. It's worth it. Get good quality materials.

Non-consumables:

It should go without saying that these materials should be dedicated to art and never used again for food.

- Pourable container: Should be able to hold at least one cup for this particular project, but maybe more if you're planning to do larger batches. Glass is best because it's super easy to clean, but plastic is okay.

- A small dish: This is to paste up the dye. My little orange dish is silicon. It was okay. As you can see, there was a lot of waste. I think next time I'll try to get a hold of some watch glasses.

- Teaspoon set

- Palette knife: Two or more would be nice. They are great for leveling your teaspoon and for making your paste-up.

- Sealable plastic freezer bags: Don't go cheap. These need to withstand a certain amount of abuse otherwise you'll have a mess on your hands, floor, and every other surface. I find the quart size to be most manageable. If you are making larger batches you can either use a gallon size, or separate into multiple bags. These can be rinsed and reused until they fall apart.

- Plastic bucket: Just to stabilize the bag while pouring the ingredients and cotton. Quart size for a quart-sized bag, gallon for gallon.

- Metal sieve: to rinse your dyed cotton.

- Tub: To soak your dyed cotton.

- Safety gear: Goggles, face mask, gloves.

- Cleanup supplies: I have one big cellulose sponge and then several sheet sponges (seen in yellow in the above photo.) I like to set my materials on the sheet sponges so any drips get absorbed instead of dripping onto the counter. (Which I failed to do in the third photo.)

What you see above includes three dried and combed examples from my latest experiment and one from the lightest result of my previous experiment. The dye I used was Dharma Trading's fiber reactive Jade Green (50). In the bottom photograph, I placed the fibers against the Jade Green swatch for comparison. From these photos it seems clear that the far left example is the closest match, but I'll add that in person, that batch looks washed out (and that may be what you want). The most vibrant and closely matched to the swatch is actually the second from the left, though in the photograph it doesn't look much different from the second to the right sample. All I can say is, look in the highlights and not the shadows, otherwise they all seem too dark.

Speaking of too dark, ha ha, check out the far right. Holy moly, what a waste of dye that was!

Speaking of too dark, ha ha, check out the far right. Holy moly, what a waste of dye that was!

|

Jade Green

|

|||

|

¼ tsp dye

per ½ cup of water

1:96 ratio

|

½ tsp dye

per ½ cup of water

1:48 ratio

|

¾ tsp dye

per ½ cup of water

1:32 ratio

|

1 tsp dye

per ½ cup of water

1:24 ratio

|

In conclusion, I will be using a 1:48 dye to water ratio (1/2 teaspoon of dye for every 1/2 cup of water) in most further projects. It gives the closest match to the swatch. It should be noted that not all of the colors require the same amount of dye. If you're buying from Dharma, colors marked with * require double the amount of dye and those marked ** require four times as much dye. If I did another batch of Cobalt Blue, that means instead of a half teaspoon, I'd use a whole teaspoon.